- Home

- Christopher K. Doyle

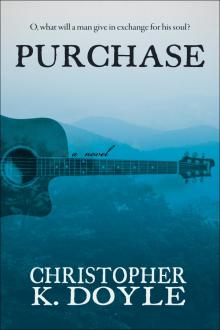

Purchase

Purchase Read online

Copyright © 2017 Christopher K. Doyle

All rights reserved.

Blank Slate Press

St. Louis, MO

an imprint of Amphorae Publishing Group

Published in the United States by Blank Slate Press, Saint Louis, Missouri 63110. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without written permission from the publisher, Blank Slate Press, LLC. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights.

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is merely coincidental, and names, characters, places, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Cover design Blank Slate Communications

Interior design by Kristina Blank Makansi

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017952355

ISBN: 9781943075409

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

To my daughter Nico

and wife Angela

(who’ve endured my singing long enough)

PURCHASE

Oh, have you seen those mournful doves

Flying from pine to pine

A-mournin’ for their own true love

Just like I mourn for mine

—Carter Family

I

Runnymede McCall and the Piedmont Pipers ~ Hemlines of the ladies ~ A cracked looking glass ~ Of Faustus ~ Bookcases and shelves ~ The words ~ Parmenides thinks not

HE HAD HEARD THE NAME WHISPERED in the shadows: Runnymede. There was music in its naming, in its repetition. A music that spilled out of the warehouses on Lombard Street, that sung from the docks lining Baltimore’s gray harbor, that hung in the placards and posters strung about the city: Runnymede McCall. Singer Extraordinaire. Lately of the Piedmont Pipers. There was a performance scheduled that night at the Peabody, and as the people waiting to enter filed up, A.D. heard in the tapping canes of the gentleman, and swishing hemlines of the ladies, a symphony already begun. Before Runnymede even took stage. It was happening, he would later tell me. The element in him had been finally raised; the excitement reaching such a peak, that he did not see himself as a derelict anymore, as a porter of detritus, wandering in his homelessness. But saw himself in the music—as the music—the music he’d hummed now for weeks outside each dance hall and soda fountain, marketplace and saloon. So that leaning up to the windowsill, he craned the cracked looking glass he’d scavenged from a trashcan just so he could see.

There were chandeliers above the stage. Green and gold confetti drifted in airy profusion. The Peabody was renowned for steeping its students in a tradition, and Runnymede certainly had his tradition down pat. Being once a student of Juilliard in New York and later the Oberlin Conservatory in Ohio, he sung from the Don Giovanni flawlessly. Then acted out a scene of Faustus with such urgency and wit that when he took a wide sweeping bow and the multitude cheered for more, it sparked such a bolt of jealousy in the boy, he suddenly wanted the life of the great man held before him. But then the Piedmont Pipers stepped from their hidden places in the wings and played a music with such pulse and feeling, the notes filtering down as if tripping from a mountain stream, that he just stood there rapt and centered, and forgot about everything else.

All the classical stuff, the high-ranging notes and lilting voice from before hadn’t moved him like these bold, bright sounds. During the previous performance he’d fixated on the lights instead. On the wide wooden stage. On the way Runnymede had of gathering in the crowd and settling them down beside him with the smooth currency of his voice. So that when Runnymede bowed again and the Piedmont Pipers—two brothers and a sister—raised their arms and waved their instruments, A.D. had to reconsider his life in accordance to this fierce new sound.

Runnymede was older than A.D., by maybe only a dozen years, but already he’d been accomplished, and celebrated as such. A.D. looked at the raggedness of his own clothing, pondered the scavenged nature of his food, and pictured a day not too far removed when he, too, might grace the boards above the crowd and serenade them with his art. Yes, his art, he muttered, for what was his art if not a singing? Or a moving forward? Moving, he thought, and listening, cataloging the complete Earth. He’d done nothing but these last four years, hearing scraps of conversation dropped here and there, picking up what others left behind. Things they only saw fit to hand him when he raised his hollowed-out eyes long enough to stare. The boy, just eighteen by 1926, learned all he could as he walked the city, pounding his shape into the solemn lines hidden beneath cotton and corduroy, denim and thread. He’d learned to become so close with his surroundings, it was easy for him to slip inside unseen as the people poured out of the performance. He wanted nothing less than to look for this Runnymede himself.

It was quiet inside the marble hall. A few stragglers purchased tickets, while still a few ushers hauled out great tattered stacks of programs with Runnymede’s smiling face on the cover. But A.D. was not interested in surveying the theater. Nor the grand arcade. Already he saw balconies in the heavens. Then he heard a single voice, lilting above bookcases and shelves with such an inflection it compelled the listener for more, holding some unutterable charm. And before A.D. could consider his intrusion, his grubby boots tiptoed his pale thin frame to the doorway to see.

It’s shit, Runnymede said, bellowing above a man whose monocle dangled to his waist.

It’s what’s agreed to in the contract. Nothing more. Nothing less.

For future returns, man. Future. Returns. In so much as to my weighted decision for returning to your fine establishment. For showcasing the prodigious vocal stylings of one Runnymede McCall. For bringing myself back to this odious establishment. The extra money is for me, my good man. How can you be so obtuse?

Runnymede was taller than A.D. thought. His rich black hair was swept up above his high pale forehead, and as A.D. looked, he couldn’t see a line or crease in the man’s whole face. It was almost as if he’d been swept and wiped clean with a mason’s quick edge. His blue suit was frosted with white piping about the sleeves, and it must have been the same one he’d worn onstage because bits of confetti drifted in the folds whenever he shook his finger in the smaller man’s face. (The Peabody’s director, A.D. would later understand, a man of much distinction in Baltimore, if not the shrewdest negotiator.)

I’ll have to check with Agnes, the man said, before hurrying past A.D. But we’ve never even had hillbilly music in here before. You should at least acknowledge that.

Acknowledge that? Runnymede turned his granite jaw to follow the man. Acknowledge that it was as transcendent as God’s green gospel? That it was more resplendent than any opera of note? That your theatergoers ate it up as if served the last supper? But the director was gone, and as Runnymede’s oratory ceased, he smiled when he saw A.D. in the doorway. The thin urchin of a boy stared at the great man and band behind, huddled in that hallowed space, the George Peabody Library. The moonlight a slight pulse in the upper windows. A frail trace of brightness and time. Something A.D. must have seen and thought upon, wondering where he might sleep that night, and if the park across the street was safe. The citizens should have that man taken out and shot, Runnymede declared. What say you about it—man? Student? Pope? How do your classmates stand that fool?

A.D.’s eyes were moist. He was so seldom spoken to—and usually only by someone telling him to move—that he suffered to hear Runnymede’s voice. How it shook the very firmament about him. How it sent up shivers in the light. Friend, Runnymede said, as he stepped closer, turning his broad-barreled chest to the boy; it’s not enough to witness the world. It’s not enough to even lead the world, I can

assure you that.

Runnymede peered down into A.D.’s eyes as the air between them became close, and a scent of ash wafted up. Wind? Did A.D. hear a rush of wind stir between them?

Change, Runnymede finally spoke, as the sounds of life and death and even breathing ceased inside the room. It’s the one true force upon Earth.

Parmenides thinks not. A.D. said, and the great man fell silent. A.D. had even silenced himself. He hadn’t seen the words rising up from inside, from all the books he’d built his life upon these years, finding them at food stalls and streetcars and in the trash heaps of the city. But there they were. They flew out into the face of what Runnymede pontificated, and as the man turned to the Piedmont Pipers, as if to persuade them to his argument, they were suddenly elated. Even stirred by A.D.’s words. As if they’d found in the boy the first instance to wound the great man they’d trudged beneath for so long. The two brothers blinked at each other like stunned owls, while the girl, the one who hadn’t even looked at A.D. before, shook her gold-hued hair at him, before turning down her face. But there was more. The great man drew himself up as if to pontificate further when A.D. cleared his throat. Parmenides the Greek, he said. That which truly is has always been.

Runnymede’s mouth gaped open, his hand wavering in air. He had reared up on his lustrous, black loafers to meet this particular challenge, but slumped down now as if taken aback by the balance of the thin odorous mold before him, this boy with a complexion like bubbled wax paper and a mealy gloss about his teeth. The man’s lips clenched in a cruel and decided crease, but he said nothing as the harried director stepped back, another fistful of twenties in his hand. Runnymede grabbed the bills and, without another word, stalked out into the street.

II

The librarian ~ Ms. Mary Frick Garret Jacobs ~ My red guitar ~ Hawthorne and Poe ~ His first impromptu performance ~ Our daily bread ~ A visitation in sunlight ~ What we need and what we leave ~ Singing honey

IT WAS THE LIBRARIAN, GOD HELP HER, who saved him. Even if I did give her a nudge in the right direction, mentioning in whispers about the boy speaking on Parmenides right there in front of her, since all she’d heard was A.D. stifling the swagger of old Runnymede. She caught A.D. by the sleeve after he’d watched, silent and forlorn, as the great man burst off from the scene, followed by the Piedmont Pipers, hustling through the grand arcade with their baggage and instruments, and A.D. thought he’d been the cause for their leaving in such a hurry.

There’s a place for someone like you, she said. Programs for which you qualify, that the great philanthropist Ms. Mary Frick Garret Jacobs put in place years ago. Being childless herself, she’s particularly fond of wayward students, and I think she’ll listen to you very well. I think she’ll help.

Now, Ms. Mary Frick had married Robert Garrett in 1872, when she was but 21 years old (and then Dr. Henry Jacobs after Robert died in 1902). But before all that, Robert’s father owned that great silver line spreading out east and west across the gathered states—the B & O Railroad—and also that red sandstone mansion right up the street. And all A.D. had to do was go with her one day to see, the librarian said. She never once asked questions about his particulars, like where he slept or what he ate, for she was known to have premonitions on students in such straights. So he sloughed off his earlier inclination toward loneliness and silence, and thought about Runnymede instead. O he thought on him and wondered how else he could ever become like that man. How else could he ever sing those songs and tread those boards, if he didn’t go see? If he didn’t try? So he did. The very next day. He looked upon Ms. Mary Frick’s gray and wizened face and repeated his story of Parmenides and Runnymede until she laughed and coughed into her hand, and that was it. He found himself on a cot that very same night, right next to mine, in the Peabody’s boiler room.

Isaiah, I said and pointed at my chest.

A.D., he said and looked at my old, beat-up red guitar before setting down a grimy bag of possessions out of which a dozen books spilled around his feet. You play?

I do. I eyed him. I’d my evening mopping to do, but was told to meet the new maintenance apprentice, as he was dubbed, before starting my rounds. Though I’d not thought to see such a one as him, all scruffed up and sooted over from head to foot, from his days spent hovelling and begging and whatever else he did. I’d not thought they’d bring me one so white neither. I mean, white as to not even look white the more I spied him, the more I considered. Meaning he didn’t have that same general whiteness as all the other white folks I’d known. That same sense of authority or standing, and probably never would. Being as he’d looked up from the bottom like me for so long. Thin as a rail, the boy had a mind on him that saw every little thing, for he noticed my stack of phonographs forthwith. Even took off the blue shirt I’d hung over my bookcase so he could assess my library in accordance to his own scattered about the floor.

I do not like that Hawthorne, he said. I do not like him at all. He looked at me and blinked, his face not moving. The cunningness of his thin nose had become amplified in the fading light. The single window looked above street level to the sky, and as the clouds darkened above us, it made me pause to see him so concentrated, almost furious in his opinion. I mean, the notion of it, he continued, that a letter, a simple stitched letter might burn on a woman’s chest for all time, designating her, that it would separate her from man and child alike. Just imagine!

Taking the canvas hat from my head, I wiped my high kinky hair and trailed a hand across my whiskered cheek and thought on him. O I thought on him and leaned to one side before finally stirring enough to address him. Designating nothing, I said. Have you read his stories?

He was quiet. Shuffling in his dirty boots, he picked through another few books before he saw one he liked and lifted it. Then he shook it out as if some certain aspect of it might flutter between us. Something he alone could detect or interpret and must have thought on for some time to say to somebody and now had the chance. Now that Poe is something else, he said. That Poe means business. He don’t fuss with all that foolishness like that other Jakes there. With all that symbolizing.

Symbolizing?

Sure.

But symbols is all they is, I said and pointed to the blue stars on the flag above my cot, and to the white bird on a poster pasted to the wall, and to a delicate few notes I’d written for a song I’d just started on a treble clef in G. Stepping closer, he studied the notes and even creased his brow before pressing his skinny finger to the paper. He sort of danced along with it then, humming with the melody that I followed in my head and stomped along to with my foot. And friends, we carried on like that for a few measures, and didn’t say a word until he stopped, humming his way to the end.

You wrote that?

I looked at him straight then. I sure did, and I rubbed my hands together as if performing some magician’s rite.

What’s it mean?

Why everything, son. It’s mine. Mine alone.

He was quiet then and looked at the notes humming his own tune, before touching the lines. Almost as if deciphering some alien landscape, something written long ago and left to dust. Something renounced henceforth from other names of people in other places. Mine, was what he heard. A word he probably hadn’t spoken since before his father had started on his long decline into drinking and drugs, like his mother before him, and what ultimately spat the boy out into the world in the first place. Mine, he finally whispered, lifting his eyes. Because I could hear it was something that stirred in him some outpouring, some idea or premonition that lingered in him even after his humming had ceased. His face was red, and as he stared at me, I suppose I was meant to know this information about him entire, that I should be informed of it for all time: Who he was. What he was. And what he meant to make with his own sound, with his incessant humming. Mine. A word he took in and ate up as sustenance itself, as another rung to incorporate into the half-won ladder of his life.

Okay, I said. That’s my music, and this h

ere’s your mop.

IT WAS ABOUT THIS TIME WE BEGAN BORROWING books from one another, me and A.D., and singing. It wasn’t easy, I assure you. He kept to himself in the beginning, and always followed at a distance, whispering some lyrics or such nonsense, humming a tune only he knew. I had to ask him about it many times, but he’d just hush up the instant I started in on him and turn his mop in the bucket, or shine another doorknob, and it was as if I hadn’t heard anything at all.

Well, I wouldn’t have none of that in my own school, mind you, where I was maintenance supervisor, so I devised one day to catch him at it. It went something like this: He filled the buckets in the utility closet with the hot water and I mopped the hallway outside it. There were a few classrooms thereabouts, and all I had to do was get him in there with a dozen buckets to scrub and inside a minute he was crooning away behind the bolted door. Well, what he didn’t know was that I had the key! And I had a way of attracting most any student with a two-step I’d sometimes do Fridays. Or before a holiday or semester break. Soft-shoeing it for the kids who thought nothing more of it than sunshine, and anyways I didn’t feel too denigrated by it. Considering I was happy to see the young people smile by my antics, for I missed that entire, the lightness of children’s laughter, that innocent charm. (Why? I’ll touch on that directly). What’s important now is the crowd I’d gathered for him, and the single key I jingled when my performance had ended, when A.D. sung out in his highest register. All I had to do was unlatch the lock and take my bow, for there he stood—singing for all his worth—before dozens of his own age, who laughed and applauded at the show.

I know, I know. It wasn’t the nicest thing to do, but it certainly wasn’t the meanest neither, and it did knock the starch out of his lonesomeness routine. For if he wanted to know everything about the music surrounding him, I did too, and thought since we were working together, it was natural enough to sing while we worked, and be friends in the process. To play back and forth with the melodies we heard in the studios and hallways that we swept through, and that ended up forming the daily ramblings of our lives. Our daily bread, so to speak. Because this was the way of the blues, I told him, when I felt he was ready. Just by looking at him I could tell he needed a good dose of the blues himself, even if he seemed to have enough of it in spades. Even if he didn’t have the first clue what to do with them.

Purchase

Purchase